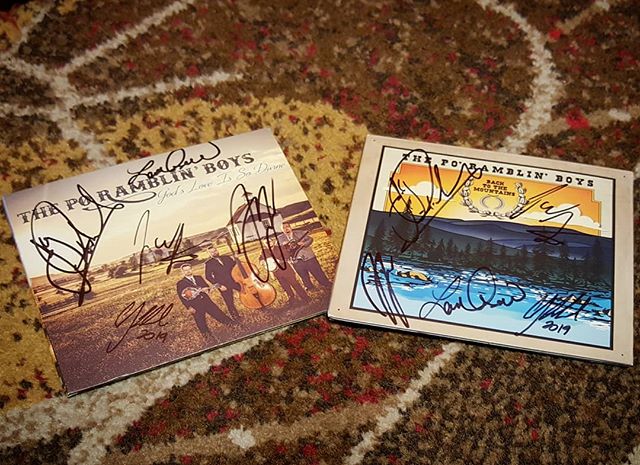

Steve Sorensen:

Finding His Own Path

by Hermon Joyner

March 30, 2015

Steve sorensen with a sprite two-point mandolin, Photo by Hermon Joyner.

Several miles north of Los Angeles in the suburban, rolling hills of Santa Clarita, California, something curious is happening. Steve Sorensen has been designing and building mandolins and archtop guitars in his converted garage for the past several years. In a relatively short amount of time, he has built his business from scratch in much the same way that he builds his mandolins—assuming nothing, considering all his options, pushing hard all the time, and making course corrections as needed—and now his mandolins are attracting a great deal of well-deserved attention.

While many mandolin builders are content to build mandolins the same way Gibson and Lloyd Loar built them, Sorensen is convinced that there must be other ways to approach the design of these eight-string instruments. In fact, it’s the design process itself that provides so much satisfaction for him. He loves it and he sums up his philosophy about mandolins like this, “I love the classic Gibson F5 design, but I’m just not interested in building copies of it.” He is quite emphatic about this.

Steve Sorensen came to mandolin building in a roundabout way. While he grew up with a dad who taught him woodworking skills, he didn’t have much experience with instrument building, aside from one banjo he built while he was in college. Even with that project, he went a bit overboard. He said, “I ended up doing marquetry on the back of the pot, with my own variation of a mother-of-pearl hearts and flowers inlay on the fingerboard and additional detailed inlays on the heel. It turned out nice, though I did fill my dorm room with sawdust.”

F8 mandolin, photo by Steve Sorensen.

Sorensen eventually studied viticulture, or wine growing, at UC Davis. When he left college, he worked at the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina, where he managed the vineyard team who developed a series of new techniques for growing fine wine grapes in the South East. However, it didn’t take long for him to realize that he was no farmer, so he moved back to LA to enroll at the California Institute for the Arts (CalArts) and got a Masters in Live Action Filmmaking. After graduating, he found himself writing scripts for a Cartoon Network’s TV show, The New Adventures of Johnny Quest, and he also tried making a feature film, but when the funding for that film fell through, he landed a job at 1-800-DENTIST, where he ran the call center for the company. What he learned about marketing in that job would come in handy when he later started building mandolins.

Starting in high school, Sorensen loved bluegrass and that was why he eventually built a banjo in college. But about eight years ago, his interest in bluegrass expanded into a new direction when he bought an inexpensive mandolin from eBay. Sorensen said, “My wife, just off the cuff, said, ‘Knowing you, you’re going to either start building these things or composing music.’ Well I’m not a composer, but I did love building that banjo. So the next week, packages started arriving at our house. It was the wood to build a mandolin.”

Since he had recently finished remodeling the inside of his house, he had most of the tools to begin building instruments. Just before this, in 2010, venture capitalists had bought out 1-800-DENTIST and terminated most of the existing management team, including Steve. Ironically, it was Sorensen’s substantial severance package which allowed him to consider mandolin building as a new career. So he picked up the few pieces of equipment that he was missing and bought a copy of Roger Siminoff’s book on building mandolins. All that was left was to start building, so that’s what he did.

Pacifica mandolin, photo by Steve sorensen.

Sorensen sees a lot in common with building mandolins and many of his other career paths. One of the aspects he enjoys the most is what he calls, “the long process.” Sorensen explains, “I realized that throughout everything I’ve ever done, there are very complex, long processes. With the wine grape process, it’s five years before you get good grapes. I did the same thing with film. I had to write my own crazy script and try to produce it. And this is the same sort of thing in building instruments; it’s the long process that attracts me. The challenge of figuring out how to make world-class instruments is infinite. It is the sum of your good decisions and your bad decisions all combined.”

And other parts of his life also feed his building process, most notably the design classes he took at CalArts, but also the writing classes and jobs he’s held. He said, “At CalArts watching great designers talk about the flow of lines and how things fit together; it changed me forever. I look at the world and I look at my designs and I’m constantly going, ‘How does this flow into that? How does everything feel more harmonious?’ I think the combination of that and my brief career in writing, where my mentors kept saying over and over again, ‘Writing is rewriting,’ and ‘Until you hit six drafts, you don’t have a first draft.’ You have to come to grips with the fact that your first idea isn’t going to be brilliant. So truly, the combination of those two mindsets means that I’m really into design and that I’m not scared to rework stuff.”

Because of his variety of life experiences, Sorensen comes to mandolin building with the right attitude, but it’s his innate nature that gives him an advantage when it comes to this business. It’s his ability to focus his complete attention on one thing and see it through to the end. Sorensen said, “My wife coined the phrase that’s on my website and t-shirts: ‘The fine line between passion and obsession.’ It came from her saying very nicely, ‘You know you’re not obsessive, you’re just passionate about things.’ I think that’s perfect for instrument building.”

custom inlay for f8 mandolin, photo by steve sorensen.

However, when you combine his obsessive qualities with his background in design from CalArts, another consequence is created; Sorensen cannot be satisfied in building another person’s mandolin design. Take his Pacifica model, for instance. The open scroll is echoed in the lines of his unique peghead, which is repeated in the shape of the pickguard. All the individual elements come together and support each other, but it doesn’t exactly look like anyone else’s mandolin and that is what drives Sorensen to build them. He’s not really interested in doing something that isn’t original. Sorensen says simply, “I love the design process.”

Picking up one of Sorensen’s mandolin, you are struck by the fine workmanship, but once you strike your first note, the quality of the sound really hits you. He describes it this way, “There are three main things. Everybody uses the word ‘chiming’ for the high notes, but Nuggets scream in a beautiful way. And particularly when players slide up the neck, they have this operatic scream that is very clear, very bright, and it makes me wonder why people aren’t playing mandolins in every kind of music, because that sound should be everywhere. Then in the mid-range, the word is syrupy. Most of the Gibson-era Loars have that mid-range richness. It’s a fullness of tone that is very complex. And then on the low end, just a straight-up woof. I work the back for that. Good mandolin backs are reactive and responsive, and that’s part of that depth. Those are the targets for me and trying to get all three? I’m getting there.”

Another place where Sorensen chooses to differ from other builders is in the idea of how the mandolin’s sound develops over time. Sorensen explains, “I sincerely doubt that the early Loars came out of the shop sounding like they do now. It takes a while to reach that complexity of sound. You can hear the years in the instrument. When I was making wine, I liked Cabernets. And a good Cabernet starts out astringent because it is high in tannins and then it loosens up over time. I think it’s similar with mandolins that if you can get the clarity and the chime in at the beginning, the looseness will grow. As a ‘child,’ I want my instruments to have all the traits they need to be a good instrument, but not to sound too old too soon.”

mandolins in progress, photo by hermon joyner.

During the building process, Sorensen likes to take his time and see how each mandolin is developing. He said, “I string up everything in the white and spend about a week or two hearing what it sounds like and then go back and thin up the back and the top from the outside a little bit and play with the graduations. After I’ve heard it and played it for little bit, I start to get a tactile sense of how the instrument is responding to the strings. That’s a time eater, but it’s worth the investment.”

It is also at this point that Sorensen draws on the expertise of his friend and mentor, Randy Torno. Torno has been playing mandolin for well over 50 years and has made a career out of teaching mandolin in the San Fernando Valley. Sorensen met him when he started taking mandolin lessons from Torno and he has become a major resource for Sorensen and his mandolins. Sorensen said, “He was the first person to support me early on and he’s been playing and teaching bluegrass forever, so it’s nice to have somebody with that much perspective. He can change modes with me and go from a player (‘I love this, it’s beautiful.’) to an instructor (‘You’ve got these things you can improve.’) to a retailer (‘If I were buying this, I’d be worried about these things.’). It’s been a great, helpful relationship.”

Randy Torno tells his side of the story, “As soon as they are strung up, I’m the test pilot. Because I’ve been playing so long, I can look at a mandolin from the player’s standpoint and point out things to him that from a builder’s standpoint he may not think are important. I feel fortunate that I’ve been in the position that I can advise him and steer him in the right direction. Whatever has happened with his mandolins would’ve happened with or without me, but maybe I’ve shortened the process a little bit for him. I think he’s going to be at the very top tier of designers and builders.”

It was Torno who suggested that Sorensen should first go to the International Bluegrass Music Association (IBMA) World of Bluegrass Festival in 2012 to show his mandolins. Torno said, “It was pretty amazing to have Adam Steffey and Doyle Lawson stop by and just freak out at these instruments. That’s what was going on at IBMA. To have these people even acknowledge our presence was way beyond what we expected, but all the major players in town stopped by and played them, and they were really very complimentary about the instruments. It was a pretty amazing experience.”

lee roy with his f8 mandolin. photo courtesy of the roys.

Sorensen worked out an endorsement at the 2012 IBMA for his mandolins with Lee Roy of the band, The Roys, an award-winning, brother-sister, country/bluegrass band. Since 2012, Lee has commissioned additional instruments from Steve, and now plays a Sorensen F8, a Sprite Two-Point mandolin, a Sprite mandola, and an arch-top Big Hammer mandocello.

With the interest in his mandolins growing in the mandolin community and custom orders steadily coming in (there is currently a 15 month wait for one of his mandolins), Sorensen is determined to remain a one-person shop, even if there can be some challenging consequences.

Such as, for the past few years, The Mandolin Store in Arizona has been the only retail dealer for Sorensen mandolins in the US, but with his increasingly busy custom build schedule, Sorensen wasn’t able to supply them with as many mandolins as they needed. Both Sorensen and Dennis Vance, The Mandolin Store's owner, thought that it was better to discontinue retail sales for now. On the other hand, Sorensen notes that he is still working with Trevor Moyle at The Acoustic Music Company in Brighton, England, to offer one or two mandolins each year for sale to retail customers outside the US.

SXS mandolin, photo by steve sorensen.

Sorensen's first set of mandolin designs included the Sprite Two-Point, the open scroll Pacifica, and the F8 model, which is his own interpretation on the Gibson F5 look and is sure to be as close as he ever comes to that model. In addition, he builds 'The Californian' archtop guitar. In 2013, Sorensen added the Sprite Two-Point mandola, and the SXS mandolin, which was inspired by the beautiful and innovative designs of John Monteleone and Hans Brentrup. In 2014, Sorensen added the Big Hammer guitar-bodied mandocello and the Big Dog guitar-bodied octave mandolin. Currently, Sorensen is building a prototype for the FX model, which Sorensen hints, "Has all the elements we love about traditional F-style mandolins and yet is totally different." If his other mandolins are any indication, it’ll be sleek and powerful, as well.

In the last few years, his interactions with working mandolin pros have taught him a lot about the directions that he should go in terms of sound and performance. Serious players know what they want and need in a mandolin, and Sorensen has been honing his understanding of what it is that they are looking for. Working to meet Lee Roy's mandolin needs, as The Roys have written and recorded several new albums using his mandolins, has been a real education. This past year, Sorensen has also been working with Randy Jones of The Lonesome River Band on an ongoing instrument project which may see the light of day within the next few months. Clearly, Sorensen delights in the long game of reworking and refining his building techniques to meet the players' needs while also delivering the rich, woody Loar-type sound which continues to get better with time.

But as Sorensen has recently finished his 50th mandolin, which is a milestone for all builders, he now knows that a mandolin doesn’t have to look like a Gibson to sound great. He is determined to follow his own path in instrument design and delights in pushing the boundaries of what the modern mandolin can look like. In fact, the last five mandolins he built are all one-of-a-kind designs, and he is happy to be working like that.

Steve Sorensen says with confidence, “I believe that I can build in the tone players want and dish up some cool new designs at the same time!”

And that’s what he’s doing right now.

Contact: www.sorensenstrings.com

[This article appeared in a different version in the Winter 2013 issue of Mandolin Magazine.]