Pava Knezevic:

Natural Born Builder

by Hermon Joyner

photo by tom ellis

Many of the famous guitar and mandolin brands have carried the names of their founders and creators. In the United States alone, Orville Gibson, Christian Friedrich Martin, John D’Angelico, Leo Fender, and Friedrich Gretsch are but a few whose names grace the headstocks of their instruments. And beginning a little more than two years ago, a new brand of mandolins was founded, Pava, which is named for Pava Knezevic. The Pava mandolins are a sub-brand of Ellis mandolins in Austin, Texas, and like many of those famous brands’ founders, Pava herself is an immigrant to the US and has now become a US citizen.

Pava’s story begins in Croatia, a country that lies across the narrow Adriatic Sea from Italy and was once a part of Yugoslavia. Pava was born and raised in Yugoslavia in the early 1960s, but in 1991, the Croatian population declared their independence from Yugoslavia, which triggered more than a decade of deadly fighting. Pava’s husband had family living in Oklahoma, so they decided to take themselves and their two children and move to the US in 1995. Pava said, “I didn’t want my kids to grow up in something like that. What happened to me didn’t have to happen to my kids. We came to Oklahoma and stayed for a month, and my husband found a job in Austin, so we moved to Austin. It is a really nice place and I love it.”

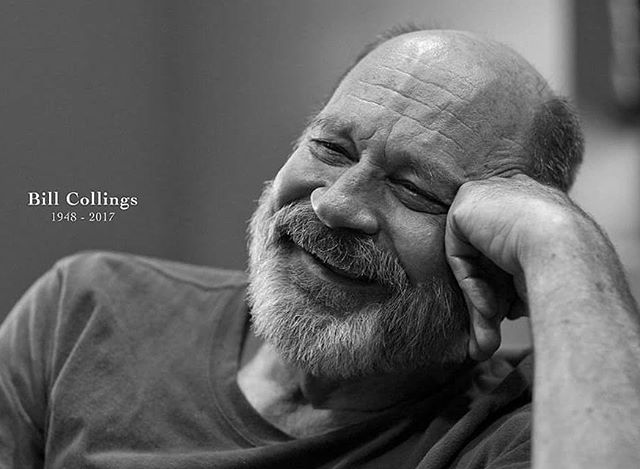

Pava had studied at a woodworking and carpentry school for four years back in Croatia, so that was the work she sought in Austin. After a few years of working in a furniture making business and even in a Walmart photo lab, she was hired at Collings to work in the finish and sanding department. Pava said, “First, I helped with the buffing and stuff like that, but after two weeks, Bill asked me if I wanted to try binding next. At first, it was a little bit scary, but I never say I don’t want to try something. I want to try everything. So I said, ‘I’ll give it a try,’ and he said, ‘Okay.’ After two or three days of putting on binding, a guy who worked there taught me how to put together each part of a mandolin from the start all the way to the fingerboards.”

photo by tom ellis

All told, Pava built a surprising number of Collings MF-5s (serial numbers 60 – 120) despite only working at Collings for about five months. But being the only woman working there was difficult, so she decided to move on to another job, though a desire for instrument building was planted in her heart. She said, “I found a job working in a cabinet building shop, but I wanted to make mandolins. I didn’t want to make any more cabinets.”

But it was when Pava was working at Collings that Tom Ellis first heard about her from Bill Collings himself. Tom said, “Bill was very impressed with her and he was bragging to me about her. And very quickly, within just a few weeks of her working there, she was doing F5 construction, binding, and assembly. Generally, people stay in the finish rub-out department for several years before they ever go anywhere else. Bill was very impressed, but it didn’t work out for her there for various reasons. Then she went to work for a furniture restoration place. I continued to ask Bill what was her story and where she was at. I did not hire her from Collings. She worked for several years in a furniture restoration place.”

Eventually, a position opened up with Tom Ellis in his Precision Pearl Inc. inlay business, which had taken over from the mandolin building that he had been doing in the 1970s and 80s. Even today, the inlay business accounts for more than 80% of the business done at Ellis’ shop, making fingerboards and headstock veneers for Collings, Gibson, Taylor, and Deering. So when Pava came to work for Ellis in 2003, there were no mandolins to be found. Pava said, “When I started working for Tom, I started in Precision Pearl Inlay, because at that time Tom didn’t build mandolins. He used to build mandolins, but he quit doing that for a while. So Tom asked me, ‘What would you think if we started building mandolins here?’ And I said, ‘Why not?’ So after two or three years, we started building mandolins.”

Tom gives a slightly different account of their conversation. He said, “When she first came to apply for a job, I showed her the shop and she looked around and she said, ‘Well, where are the mandolins?’ So I explained to her that I didn’t make mandolins anymore, but I used to. And I remember that was the very first day she was out here, she said, ‘Well, we should make mandolins.’”

In fact, Tom had been thinking about getting back in the mandolin building business. It had been 15 years since he had given it up, but he knew that he couldn’t do it the old way. It just wasn’t cost and time effective. But by the 2000s, there were CNC (Computer Numeric Control) machines to automate some of the steps. The only problem was that Tom didn’t know anything about programming them. But he was soon to have help. Nathan Arrison, the man who set up Collings’ system, was available and Tom began talking to him.

photo by tom ellis

Tom said, “When Pava started here, I started consulting with Nate about translating my drawings into tool paths so we could start machining some of these mandolin parts and get rolling. Not very far into it, I realized that this was going to be a pretty big job. So Nate came to work here about three years after Pava did. He was single-handedly instrumental in developing the mandolin manufacturing system that we use.”

Now all the pieces were in place for building mandolins again and one thing led to another. Tom said, “So the three of us basically dived into the mandolin project, which started out being only Ellis F-models. Subsequently, after the recession, we came out with the Ellis A-model and almost two years ago—IBMA year before last—we debuted the Pava A-model and we’ve done over a hundred of them. That’s going quite well. They’re coming out real nice and the talk is real good on them. The plan is that I won’t have a hand in them, eventually, though currently I still do, and about six months or so ago we hired Christian McAdams, who worked at Collings for three years mostly in the finish department, and that is mostly what he’s doing here. He has been working towards doing the assembly, binding, and sanding of the Pava’s—a lot of what Pava has been doing all along—and that’s going to allow her to move to the final set-up, and also her and I can concentrate on the Ellis mandolins, which historically we have been splitting up the work 50-50.”

There was a practical reason for naming the new line, Pava. Tom wanted to keep the Ellis line a premium line of mandolins and didn’t want to make a entry-level Ellis. He said, “I, at least in my own ego, want to feel like I’m high-end and I want to stay that way. I never wanted to play in the $3000 market under my name and it kind of left us in a bit of a bind. You don’t have to look very far to see that pretty much all mandolin makers are trying to come out with what you’d call a stripped-down, discount model.” Tom didn’t want to play that game.

Ellis mandolins had seen their demand decline sharply in the years after the last recession. He and Pava went from building 50 F5s a year to building just 12. He had to do better than that, and that was why they came up with the Pava. To say that this is an unusual move is a bit of an understatement. Few, if any, companies create a new brand and name it after someone other than the owner of the business. Tom said, “It’s not only unusual, I think it’s unique.”

photo by tom ellis

Pava added, “Two years ago Tom gave me the opportunity with my line, a line with my name. I don’t believe that anybody else would do that; only Tom would do that. Just give someone who worked for him his own line of instruments. It’s because he believes in me. He said I’m doing good and we can do this. And it’s like, well, our instruments have proved themselves.”

Tom said, “You can go back in the history of guitar companies and many of the successful ones, if not most, carried the name of the founder and the name of the person who actually made it. If you buy a Pava mandolin, Pava made it.”

At the moment, there are three models of the Pava: the Satin, the Player, and the Pro-Player. Each one has a progressively greater level of finish and binding. The Satin has the least with a matte finish and only a single-binding on the top, and the Pro-Player has a gloss finish with full triple-binding. And there are four finish color choices: brown, amber/orange, blonde, and sunburst. For now, there no plans to produce an F-model mandolin. Pava said, “I’m pretty busy with the A right now.”

And although Pava mandolins number around 107 or so, Pava herself has built far more than that. Tom said, “Pava number one was really number 250. We weren’t experimenting; they’re basically the Ellis A-model for all practical purposes. We didn’t change anything, though she does the top and back graduating, instead of me.”

For Pava, it’s all about perfecting the skills for building mandolins. That’s the benefit of restarting the Ellis brand years before beginning her own. She said, “It gave me the time really to perfect those skills. And when you carve the tops and the backs, you have to really feel it. Because in everything you start, anything you do, every time you do it, you try and push yourself to learn more and make it better and better.”

Both Tom and Pava have different opinions on how the Pava mandolins are different from their Ellis counterparts. Pava said, “Right now, it is so easy for me because every time I carve the tops and the backs, I know exactly for what I am looking for and I can feel it with my hands. His sound different because Tom does the tops and backs. I probably will never be able to do that just like Tom. His mandolins sound much better than Pavas.”

photo by tom ellis

But Tom said, “They’re really quite similar. We limit our models and limit what we do, and only use red spruce for the tops, but we do vary the back wood. The Pava backs are almost always red maple and mine are virtually always sugar maple. So sound-wise, you do get that difference. Sugar maple ones are hotter, poppier, with more projection, and the red maple ones are warmer and rounder and sweeter. This year, probably the top two or three sounding mandolins that have gone out of here, may have been Pavas.”

Starting a career like instrument building when you’re close to 40 may seem like a stretch to most people, but for Pava Knezevic, it was like coming home. She’s as good a case for there being “naturals” as any you’re likely to hear, because there’s little else to explain how she could learn and master the process so quickly in a matter of weeks. But the other part of the equation is that she is incredibly hardworking and she never gives up on anything she’s set her mind to.

photo by tom ellis

Tom Ellis describes Pava like this, “Not only is she a natural and extremely meticulous and a real problem solver, but she’s the only person that I’ve ever met who, on a regular basis, gives you an honest 60 hours of work in a 40 hour week. Pava is one in a million. She could not be replaced. There’s no one else like her.”

But Pava takes a somewhat more matter-of-fact approach to herself. She said, “I never give up. I have never give up on anything in my life. If I have a goal, I will finish that goal. The Pava mandolin is a good mandolin and I will try to make it the best that I can.”

And when she says that, you know that she will deliver on that promise and her “best” might just be the best mandolin of all.

[Author’s note: Some quotes in this article have been edited for consistency.]